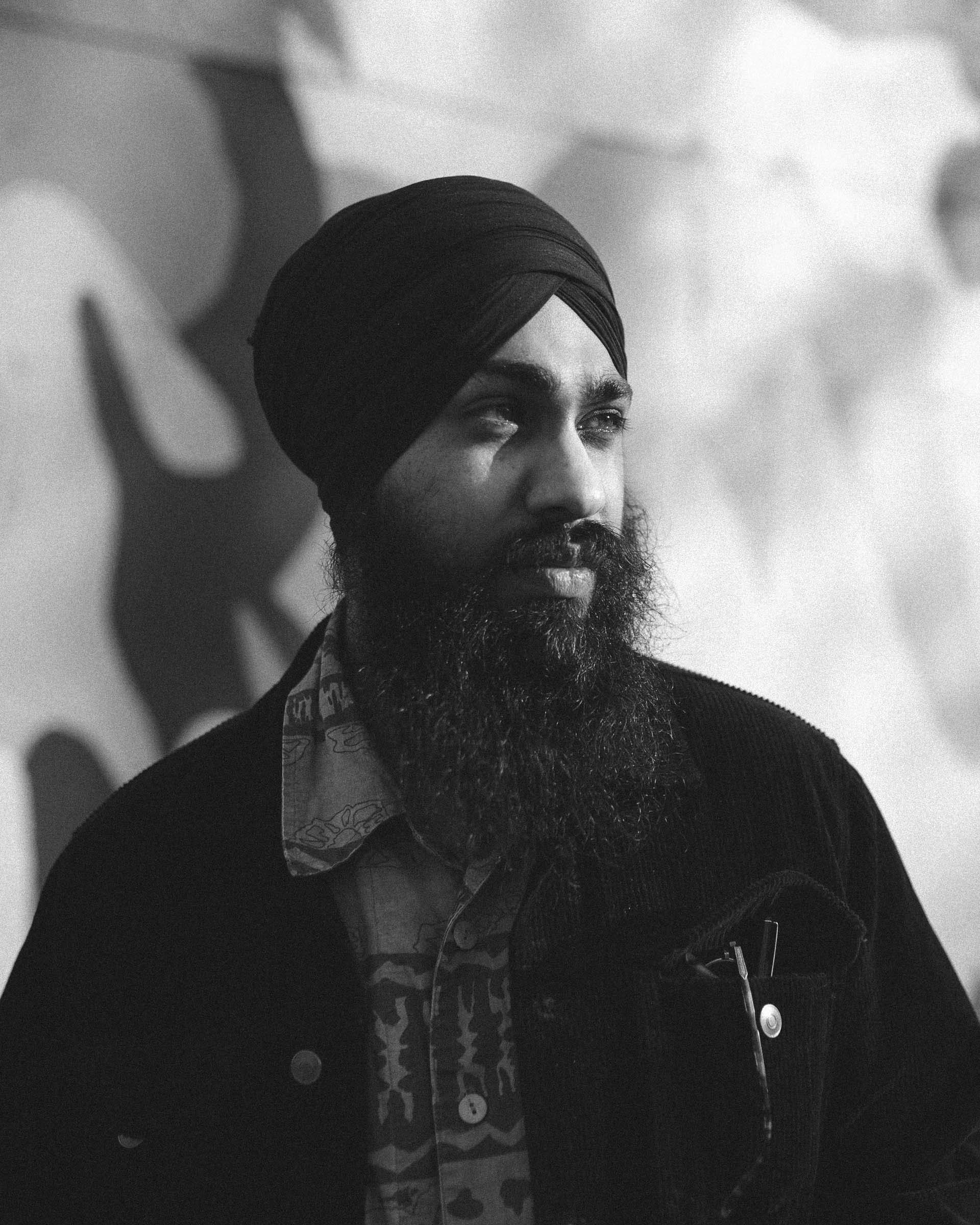

Imroze Singh Goindval

To me, being a Public Scholar means moving knowledge out of paywalled journals and into kitchens, clinics and gurduars (places of worship). It’s designing questions with communities rather than about them; treating lived experience as theory-rich and holding myself accountable for usefulness, not just novelty. Rigour shows up as transparency and ethics; impact shows up as reduced stigma, earlier help-seeking and tools people actually use.

Research description

What does being a Public Scholar mean?

To me, being a Public Scholar means moving knowledge out of paywalled journals and into kitchens, clinics and gurduars (places of worship). It’s designing questions with communities rather than about them; treating lived experience as theory-rich and holding myself accountable for usefulness, not just novelty. Rigour shows up as transparency and ethics; impact shows up as reduced stigma, earlier help-seeking and tools people actually use. In practice, that means co-creating Panjabi resources, making everything open-access and iterating based on community feedback. It also means changing the university from within — recognizing plain-language videos and guides as legitimate scholarly outputs and mentoring peers to do knowledge translation well. Ultimately, a Public Scholar returns knowledge to the people whose stories make it possible — so research doesn’t just describe the world; it helps heal it.

In what ways do you think the PhD experience can be re-imagined with this Initiative?

The PhD can be re-imagined as a community co-lab, not a solo marathon. With PSI, I’d normalize structures that make scholarship legible and useful to Panjabi communities: (1) build Community Advisory Boards into programs from day one — budgeted for honoraria and translation; (2) treat transcreation (Panjabi-English videos, guides, WhatsApp blurbs) as core scholarly outputs, archived alongside the thesis; (3) require a plain-language and Panjabi summary of every chapter; (4) replace one traditional seminar with a community practicum hosted by partners; (5) allow mixed-format dissertations (articles and knowledge translation portfolio and reflection on ethics and power); (6) invite community reviewers to comment on relevance, not just methods and (7) add language access and culture-centred design modules (e.g., working with concepts like izzat (honour), seva (unconditional service), sangat (community), and incorporating story circles/faith-based venues such as gurduaras). A PSI-shaped PhD would measure success by rigour and resonance: do families understand it, can providers use it and does it create understanding? That’s the kind of training that prepares scholars to serve the public — within and beyond the university.

How do you envision connecting your PhD work with broader career possibilities?

I see my PhD as the launchpad for Kosh Health, a Panjabi Health Communication Lab that turns research into practical tools for families, clinicians and schools. In the near term I’ll work as a knowledge-translation lead in a health authority or large community agency, scaling Panjabi-English transcreation toolkits on mental disorders across communities — while teaching as a practice-focused faculty member. Kosh Health will anchor both paths: (1) a research-to-resources pipeline built from my PSI portfolio; (2) teaching and mentorship, including practice-based courses in culture-centred design, language access and CBPR, with community practica and (3) systems and policy advising, producing plain-language briefs and open educational resources that ministries and health authorities can adopt.

How does your research engage with the larger community and social partners?

I work with Panjabi communities and service providers from the outset. We co-design plain-language, culturally resonant materials; test early drafts with a small advisory group and refine based on practical feedback. The resources are shared through everyday community settings (e.g., faith spaces, schools, clinics) and released open-access so others can adapt and use them. Whenever possible, I also offer brief “how to use this” sessions so frontline staff feel confident introducing the tools to families.

Why did you decide to pursue a graduate degree?

I pursued graduate study to turn frontline experience into structural change. As a medical interpreter and KT specialist, I saw how Panjabi families hit language, stigma, and system barriers. A PhD gives me the theory, methods, and partnerships to build practical tools, inform policy, and teach the next generation to do community-engaged, culturally safe public health.

Why did you choose to come to British Columbia and study at UBC?

UBC sits where my work needs to happen: Metro Vancouver’s large Panjabi communities, partners like Fraser Health/BC CDC and a public-health ecosystem.