Universities have largely benefited from an extractive model of research on Indigenous communities. In decades past researchers would visit Indigenous communities to conduct their research, and publish their results afterwards – often without consulting with the community, providing a chance for review, or providing copies of the data or final publication to the community. This extractive model of research can often make Indigenous communities wary of new community partnerships with universities and students in general.

But in the age of reconciliation, we need to switch to a new model, where communities are consulted, and relationships are reciprocal, ethical and not extractive. One where Indigenous Peoples can choose the types of research projects that are important to them and determine how they want to collaborate.

Indigenous communities have long held a deep connection with their natural surroundings, utilizing resources in sustainable and culturally significant ways. In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of engaging with Indigenous knowledge and collaborating on research projects that address their needs and aspirations.

For Indigenous History Month, we highlight UBC graduate students who are working with communities on projects related to sustainability, from both a traditional and modern perspective.

Marina Mehling and Lizeth Ardila are working with Indigenous communities in unique ways – learn more about their research.

Marina Mehling

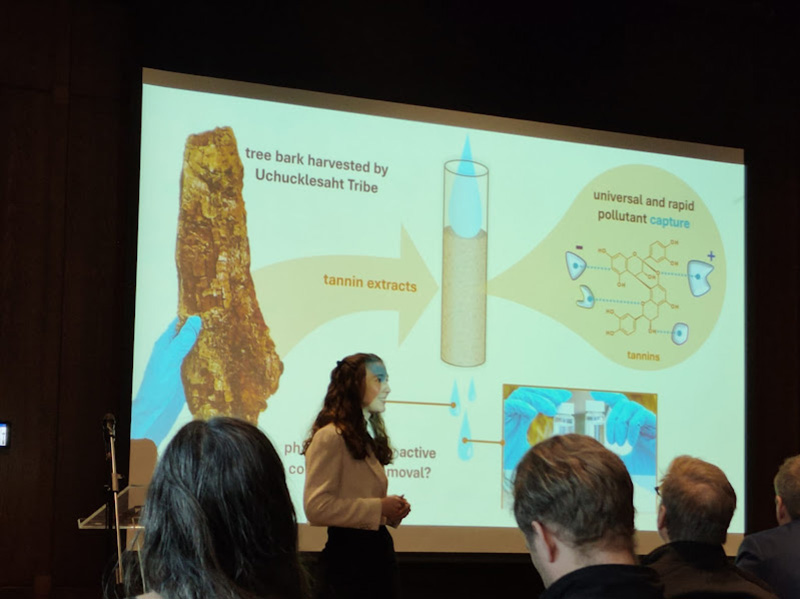

Marina Mehling, a PhD student at UBC Chemical and Biological Engineering, is unlocking the potential of Western Hemlock bark. Her project, in collaboration with the Uchucklesaht Tribe, aims to use this bark to address water pollution. The initiative is part of the BC Ministry of Forests Indigenous Forest Bioeconomy Program, which supports sustainable practices with Indigenous-owned forestry resources.

Photo by Marina Mehling.

Western Hemlock bark is rich in tannins—compounds traditionally used to tan animal hides and cherished for their cultural and medicinal significance in various Indigenous cultures. However, Marina's interest lies in the modern applications of tannins, specifically their ability to purify water.

"Tannins excite me because they are excellent at capturing pollutants that conventional wastewater treatments can't handle," she explains. Her project focuses on the bark's potential to remove selenium from mining effluents, a challenging pollutant.

The journey began when Marina's professor, Orlando Rojas, was approached by the BC Ministry of Forests to propose ideas for utilizing tannins from Western Hemlock bark. With her previous experience in tannin-based technologies, Marina eagerly took on the challenge. She presented several potential applications to the Ministry and the Economic Development Managers of the Uchucklesaht Tribe and Port Alberni, ultimately deciding to tackle water pollution together.

“I initially proposed several tannin-based technologies to the BC Ministry of Forests team as well as the Economic Development Managers of the Uchucklesaht Tribe and Port Alberni. Together, we decided to tackle water pollution with tannins. I particularly enjoy that my work can impact a community within BC,” Marina recalls.

What's particularly rewarding for Marina is the project's potential impact on a local community. "It's exciting to see my work making a difference within British Columbia," she says. Through regular meetings and open communication, she ensures that the Uchucklesaht Tribe's insights and feedback are integral to the research process. This collaboration exemplifies how traditional knowledge and scientific innovation can come together to address environmental challenges while supporting Indigenous communities.

Lizeth Ardila

Lizeth Ardila, a Master's student in Integrated Studies in Food and Land Systems at UBC, is dedicated to addressing food insecurity within the communities of Indigenous, Black and People of Colour. Her journey began during the 2020 pandemic when she encountered the Deer Spirit Permaculture Garden in her Winnipeg neighbourhood. This garden, led by Indigenous Knowledge Keeper Audrey Logan, provided crucial lessons on self-sufficiency and food security.

Inspired by Logan's efforts, Lizeth's research evolved from urban agricultural projects to a broader investigation into how Indigenous and communities of colour are tackling food insecurity. She focuses on urban agriculture projects, community gardens, kitchens, advocacy groups, and non-profits. Lizeth believes these stories need to be highlighted to support these historically underfunded and food-insecure communities.

Building trust and collaboration with Indigenous communities has been central to Lizeth's approach. Her work with the Jane Goodall Institute of Canada, which emphasized decolonization and reconciliation, taught her the importance of relationship-building and reciprocity. Lizeth emphasizes that research without trust and understanding is futile. She believes it's crucial to build relationships with transparency and learn from the communities without expecting them to teach everything.

Although she herself is not Indigenous, guidance from her Indigenous supervisor and community members has also been invaluable. Their leadership and advice have significantly reduced challenges in her research. Listening to their experiences and accommodating their needs has been crucial to her success.

One of the most impactful moments in Lizeth's research was organizing a gathering at an Indigenous restaurant in Winnipeg. This event allowed participants to share food and discuss their experiences, fostering new connections and rekindling old ones. "Seeing people reconnect and build new relationships was beautiful. It was one of the outcomes I hoped for, fostering connections and reciprocity," she recounts.

Rainbow Community Garden. Photo by Lizeth Ardila.

Lizeth is committed to ensuring her research benefits the communities involved. She plans to develop reports that can be presented to policymakers, highlighting the realities of these communities and advocating for change. Lizeth's work is guided by principles of ethical research and positionality. Understanding her role as a settler and a person of colour, she strives to separate her experiences from those of her participants. Her supervisor and community members help keep her accountable.

Lizeth's focus on relationship-building and cultural sensitivity exemplifies a collaborative and respectful approach to research. She advises new researchers to prioritize building relationships.

“It’s important to let them know that their knowledge is theirs, and I’m just a tool to bring their knowledge to a setting, like Winnipeg to UBC. I hope to be that bridge to highlight their voices, but at the end of the day, it’s their voices,” said Lizeth when she talked about the need to amplify the Indigenous voice in research.

Photo by Lizeth Ardila.

Building trust and reciprocity

Marina and Lizeth’s experience highlights the potential of blending Western research with Indigenous knowledges to address pressing environmental and social issues as it illustrates the profound impact of respectful and reciprocal collaborations between researchers and Indigenous communities.

As she attended the workshop co-hosted by Emily Carr and the BioProducts Institute, Marina was enlightened and humbled by the knowledge that non-scientists possess – including Indigenous Knowledge Keepers. As she reflects on her research project, “... artists, trades workers, and Indigenous Knowledge Keepers have developed wonderful techniques for manipulating and working with trees in harmony. There is much to learn from these experiences, and we must be willing to look beyond academic journals to find them.” She finds that having an open mindset and respect for diverse forms of knowledge are crucial for meaningful and impactful research.

Lizeth also speaks to the importance of relationship-building and reciprocity in community-engaged research. “To have an understanding that decolonization is not something you just do one paper, but something you enact. And enacting that means, again, building relationships and trust – it’s one of the ways but not the only one,” says Lizeth. Her emphasis on the collaboration between researchers and the Indigenous communities has enabled her to learn about what the communities involved in her project truly need, ensuring that her work benefits them.

Photo by Marina Mehling.

For future graduate students interested in working with Indigenous communities, the first step is to speak with your graduate advisor, professor or program office to determine what might be possible for your program. Be prepared to do some research. You can consult one of the many on-campus resources such as the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, the First Nations House of Learning, or Indigenous.ubc.ca. Marina, Lizeth and G+PS staff have suggested a few resources below.

Recommended resources for students interested in research with Indigenous communities

- Carroll, S, et al. 2020. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19: XX, pp. 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-042

- "The First Nations Principles of OCAP®” First Nations Information Governance Centre. https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/objects/9629

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (S.C. 2021, c. 14). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/U-2.2/page-2.html#h-1301627

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions, 2015.

- Musqueam First Nation. Place Names Map. https://www.musqueam.bc.ca/our-story/our-territory/place-names-map/

- Resources for researchers. Indigenous Research Support Initiative, UBC. https://irsi.ubc.ca/researchers/resources

- Indigenous Forest Bioeconomy Program. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/supporting-innovation/ifbp

- “Where are the children” virtual exhibition. https://legacyofhope.ca/wherearethechildren/